As the darkness of night broke into the dim light of dawn, a mist hung over the landscape like the woollen blanket that had hung over my head only thirty minutes earlier; reluctant to be removed but resigned to the inevitability. An early September morning on the Isle of Gigha and we have five days to search for a legendary Spanish ship, provide a basic survey of a potential crannog (i.e. Scottish lake house built on stilts), and do a general walkover of the island, on the lookout for any oversights to the coastal heritage.

Cylinders clinked into place as buckles and straps tightened, a few boxes of extra supplies tucked into a dirty corner of the open-bed trailer and scuba sets carefully strapped onto the sides where they seemed least likely to get dirty or damaged. Drysuits, rock boots and snorkels carefully stowed at the back of the trailer for a quick change before we set off: a day’s work before 6 am.

Now the team turned to its final morning agenda: breakfast. Willie McSporren – you couldn’t make that name up – had seemingly been awake for hours before everybody else. From the moment of awakening, we were all caught by the thick and heady smell of sprats being fried in butter, bread toasting in an over the fire, wire cage. Buttered sprats: the McSporren household’s answer to a vegetarian diet. He’s our host. What can you do?

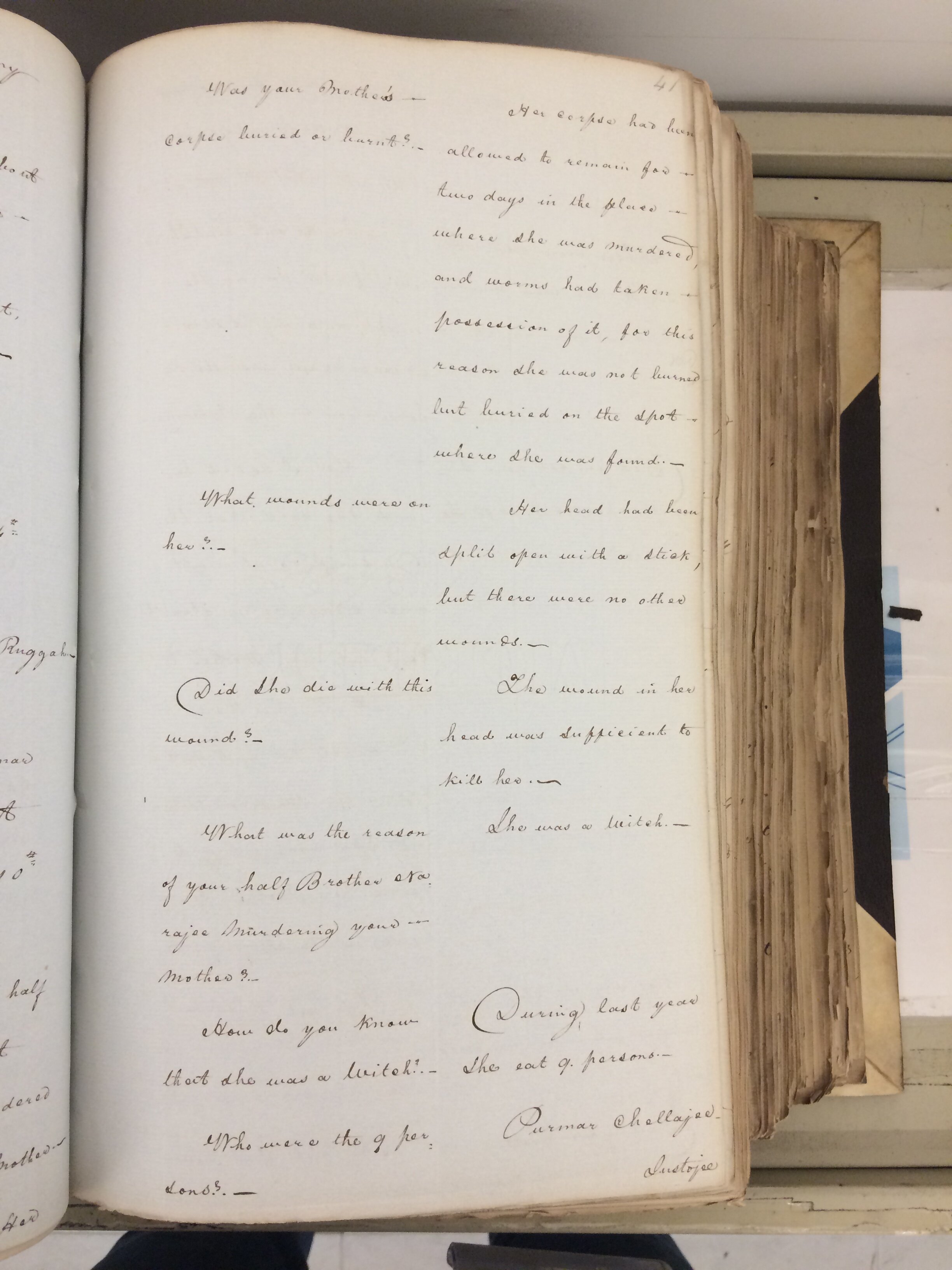

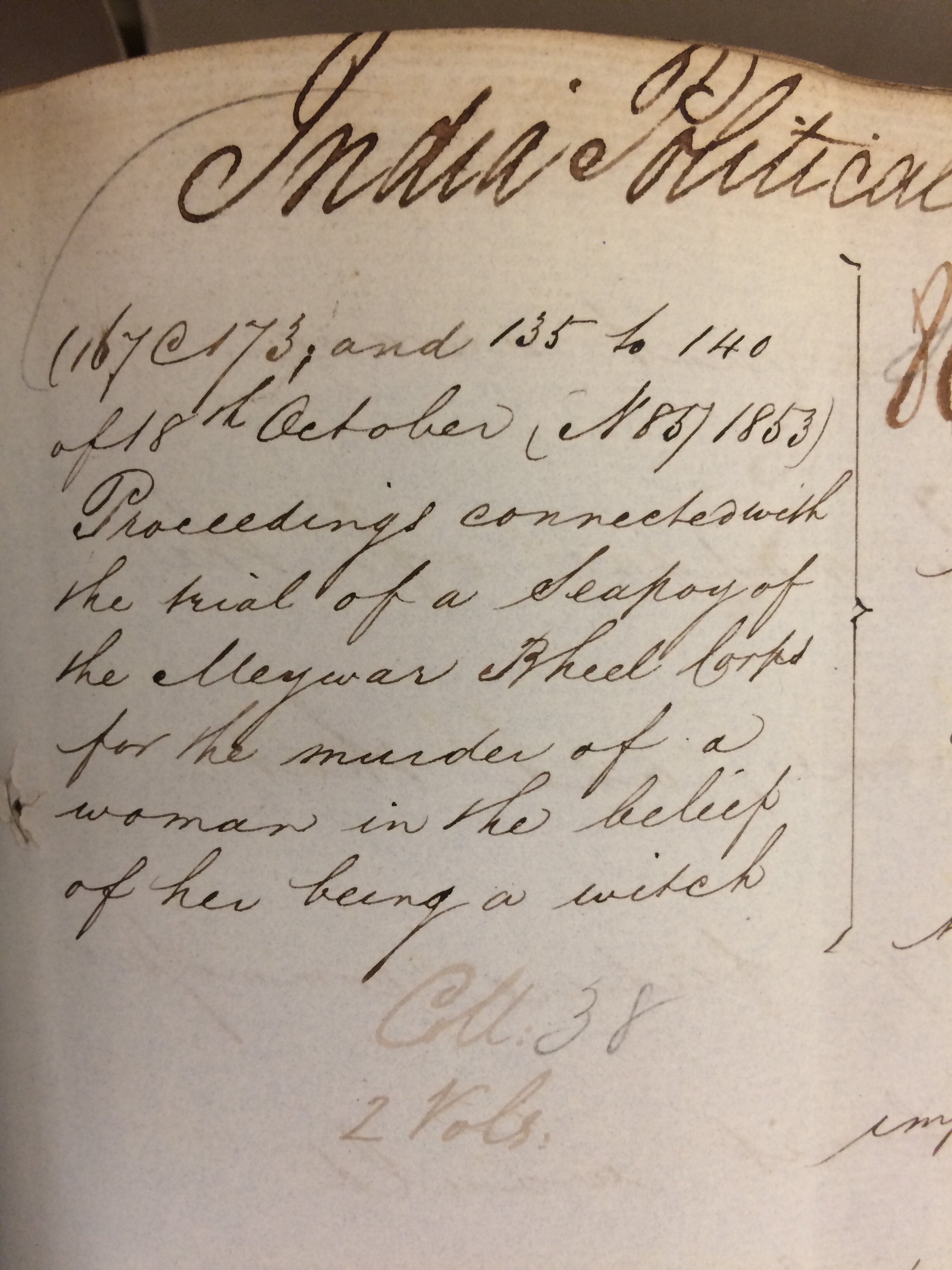

Crusted bread topped in wet sprats, eyes still gleaming, tossed down with regrettably none of the smoky whisky of the previous night, we returned to the day’s main point: surveying the coastline for the Esperance, a legendary vessel wrecked somewhere off the west coast of the island. There had been a mutiny on board, the captain killed, along with his wife and two other crew members. The remaining crew lost control of the ship. Upon finally making it to shore, there was a scuffle over who would take the coin purse, allegedly full of Spanish gold and silver coins. In the chaos, the purse was flung into the sea. Hamish’s great uncle had once found not one, but two, ‘Spanish Doubloons’ on the west coast. They became the pendant of a local woman’s necklace, though of course the necklace had since been lost, and nobody could say exactly where those coins had been found.

The mutineers ran through the dark of night to the Tarbert farm, some making their way to other ports, never to be heard from again, while the others?… Magnus’s older brother swears that they’re the descendants of one of the marooned sailors who took up residence and dairy farming on the island, marrying one of the daughters and accounting for Magnus’s dark hair and olive complexion. His family gave an artefact from the Esperance, a powder horn, to another local woman as a gift many decades earlier. The horn is said to be in her possession, but its exact location within her belongings cannot be established. One of the dairy farmers that we run into on the pathway to the trailer contends that on stormy November evenings, you can see the outline of the ship on the horizon, just off the coast at Port Ban.

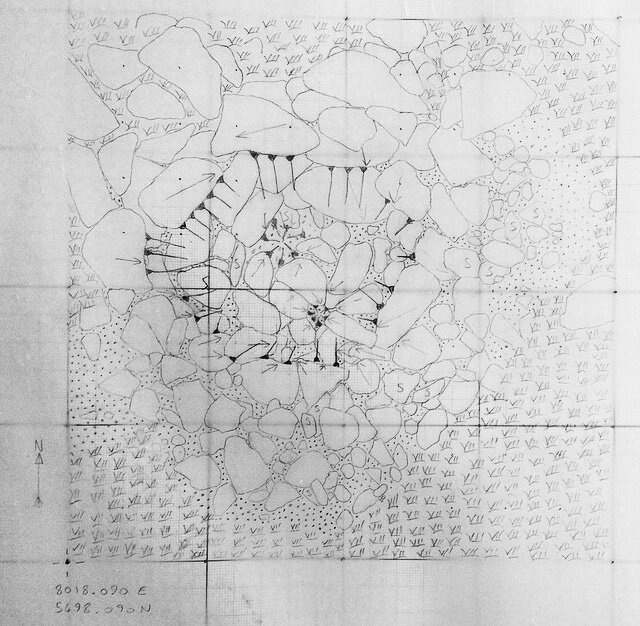

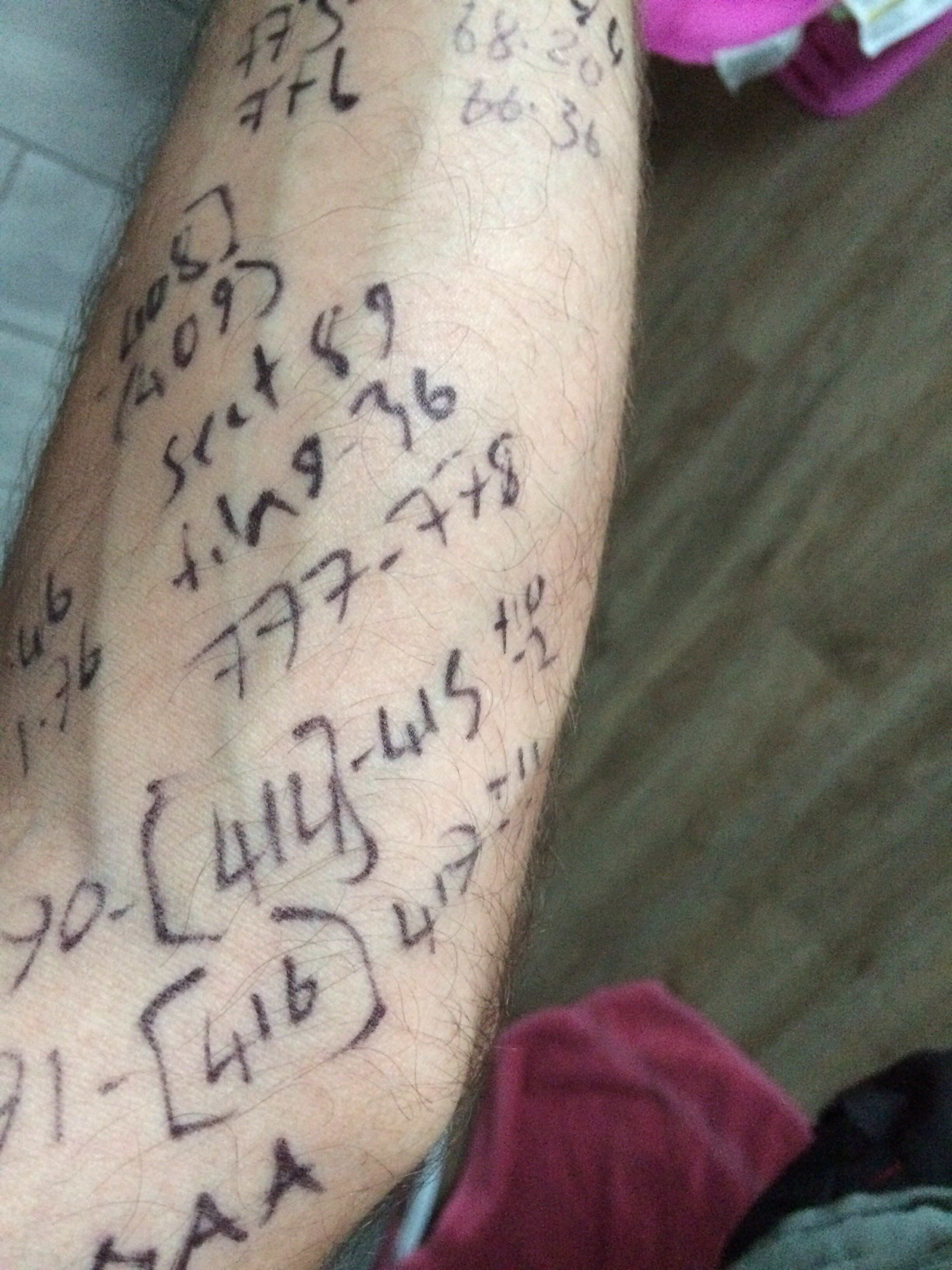

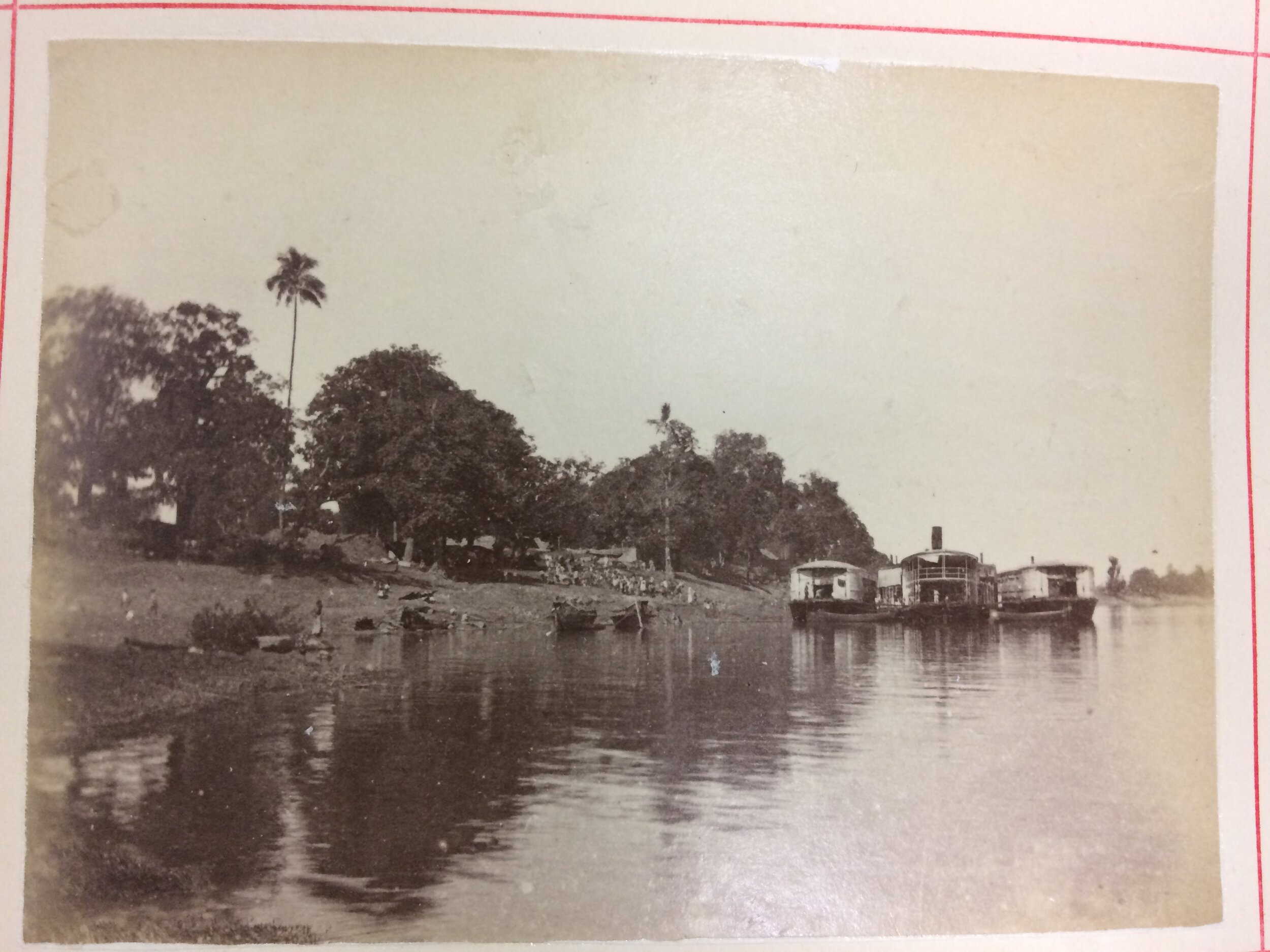

Based on the stories surrounding the Esperance, the team had been weeks in preparing for our excursion. We had painstakingly checked the online Canmore records, gone over historic maritime charts, asked around the Edinburgh museums for any information related to the vessel. There was very little information, so this trip to Gigha would be its own recce in the truest sense. A week earlier, we had all sat around the training table at the dive office, discussing logistics and planning our schedule: meet and greet the islanders (all 100?), a day of diving, two days on coastal surveys, one day on a walkover. Finally, the big day had come and we had loaded the dive van full of kit, archaeology supplies, our maps and records, camera equipment and plenty of spares of everything – there were no air fill stations or ScubaPro repair shops on Gigha. After an hour of the gentle ferry ride, we had finally come into port at Ardminish, greeted by ‘the man from the big house’, our host Willie McSporren and the man who invited us to the island in the first place, an acquaintance (now the mayor of Gigha) I’d known from Edinburgh.

As the ferry pulled away and we looked about the island, we had no idea what the next day would bring, but for this night we would enjoy the hospitality of our hosts and draw up a plan for tomorrow’s big dive: our hunt for the Esperance.

To be continued…