Dearest Emily,

I apologise for the paucity of correspondence of late, the overwhelming magnitude of material from which I have had the pleasure to examine has kept me incredibly busy. You will no doubt be delighted to learn that during my time at the British Library, I have been positively rewarded with untold treasures from within the dusty tomes of that opulent labyrinth.

Here I shall recount an alluring discovery and intriguing trail. I am certain you are eager to learn of my latest expedition through these folios of fascination, therefore I shall not hinder your curiosity any further.

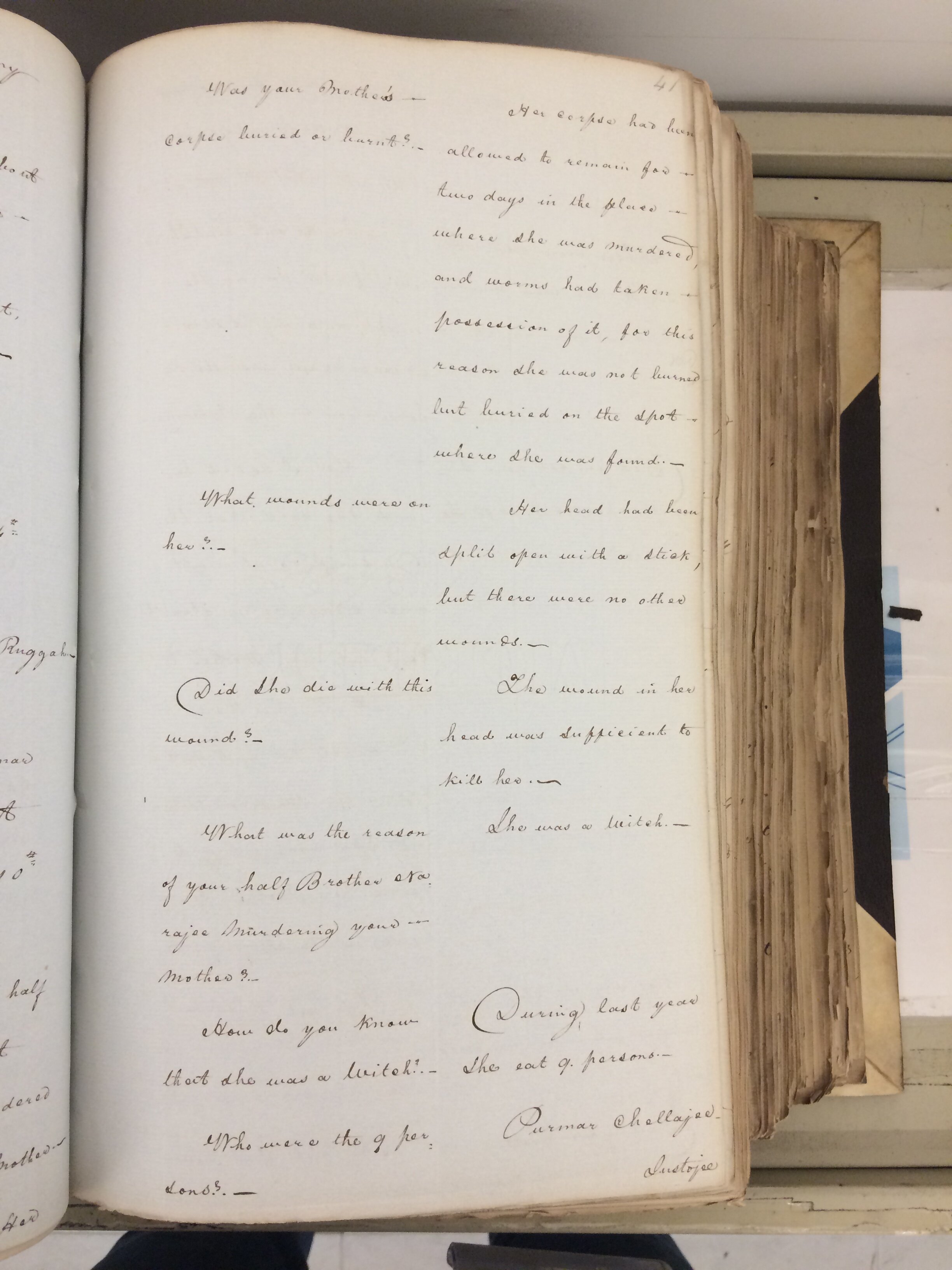

Some time ago, whilst trawling the meticulous and compelling archives of the Hakluyt Society, and preparing documents for public consumption, I came across a unique package of seemingly unanswered correspondence.

One letter in particular, addressed to the president of the Society, had been sent from a certain Phillip Swann who had undertaken an adventurous sojourn through South America during the 1930’s. On his travels, he and an accompanying Scottish mining engineer were introduced to a humble local family who produced a bundle of documents, apparently the private papers of a secret society known as La Socied de la Doble Cruz.

The Society of the Double Cross!

Now as you are surely aware, I am justifiably dubious when it comes to secret societies and treasure maps, often the work of fiction and fantasy. Yet I was intrigued by the curiously out of place document and made a decision to delve further.

Mr Swann proceeded to describe a number of translated documents referring to various hordes of stolen booty hidden across a multitude of Caribbean hideaways. It name dropped such legendary figures as Montezuma and Sir Henry Morgan and promised, should the strange hieroglyphs appearing throughout the document be understood, potential lost fortunes might be recovered.

“The papers were found in the shape of a ball, covered with (bitumen) and fastened with two gold pins. There was also ten small bars of gold, one semi-precious stone, four minted coins very poorly done, a very big key, four or five weights (presumably for weighing gold) a bundle of papers wrapped in a sort of wax and a skeleton with a nail in the head.”

Why you may ask, did Phillip Swann not go on to discover these wondrous treasures? He may well have? I could find nothing further on the gentleman from the scant information at my disposal. He did however give reason for the apparent pause in his research.

“Over a period of two years, my introducer and self, did what we could to investigate the matter, but were hampered by the fact that they did not really trust us, as a considerable number of the documents had already been filched by people they had consulted. I left South America; the war came along, and it is only now, in my retirement, that the interest has become aroused again”

Swann provided a list of potential targets mentioned in the papers, which he hoped to explore further. These included the Booty of Mexico 1635, activities on the Lake of Maracaibo, The Secrets of the Vulgate, The Oath of Istanbul, Buried treasure on the Island of Cuanacoco and an Irish built warship, the K.H-erye, amongst others.

Swann suggested the then President of Venezuela, Vincente Gomez, had financed an expedition in search of the related treasures, but believed the lack of media coverage indicated little if anything had come of these expeditions.

Armed with this letter and little more I decided to do some investigation of my own. Whilst the Society of the Double Cross failed to secure any hits on our catalogues or produce any contemporary references, the vast ocean of information that is the World Wide Web provided some tantalising leads.

The first involved the famed ship wreck salvager and American treasure hunter Arthur McKee. Art had a history of success finding relics of ancient vessels and the plundered riches of bygone eras. His notoriety in such expeditions led to advice and accompaniment being sought on all manner of similar adventures. In his journals, Art documented an experience whereby:

“I was contacted by two men from Venezuela who stated that they wished to discuss with me some strange markings which they had found on some old documents. These documents were discovered at an old house in Venezuela which had been torn down.”

The journal goes on to describe papers “inscribed on a skin-like material and leather and dated as early as 1557” many of which referred to The organisation of the Doble Cruz. It described the same marks and Hieroglyphs mentioned in Swann’s letter, but Art also found “…a faded but identifiable document which contained one of the coded alphabets”.

Art McKee’s translations mirrored the writing of Swann in a fashion well beyond mere coincidence, dates and names being repeated, but there were just enough slight translation discrepancies to suggest this wasn’t a copy of earlier research. He appeared to be witnessing the very same original documents.

McKee would take the challenge a step further, selecting one of the potential targets to conduct an expedition. He chose the Forte La Tortuga, a Pirate Fortress located about 110 miles off the coast of Venezuela. He was joined on the expedition by Professor Alberto Cribeiro Valiente and his son, who were all dropped on the deserted island by helicopter with a promise to be picked up 7 days later. I shan’t go into the details here, the full story can be found online, but the expedition was a disaster. Injury and disorientation from day one led to a very real fight for life, McKee was stranded alone in the searing heat of day and freezing cold of night, with little shelter he survived on nothing more than cactus juice and his fast fraying wits. Eventually, the Army led a rescue 10 days later. The original quest was abandoned and never again attempted.

So another dead end perhaps, but a final trawl of the internet brought my research right up to the present day. Of all the bizarre places you might imagine discovering an ancient secret society of Pirates, Facebook would not seem the most likely, but there it was, a page dedicated to La Orden de la Doble Cruz.

Once again the page described similar aspects, names and places as the previous sources, but in a new, even more inconceivable twist, the Society were now linked to the Illuminati Templar Order! The page offered welcome to the fraternal Brotherhood around the globe via their Gmail account, pleading their legitimacy… “evidenced by authentic ancient documents that rest in this city of Maracaibo of the Zulia State, in our beloved country Venezuela.”

So… do the documents exist? Who knows? The archives and libraries of Maracaibo could be scoured, perhaps the documents lay waiting to be fully understood, their tantalizing treasures begging to be finally uncovered?

If you find these swashbuckling tales have tickled your fancy, and should time permit, you might be enticed to dig deeper, for as our curious and compelling mystery provider begged of the Hakluyt Society all those years ago,

“Even now, I still feel there is a glimmer of truth in it all, and it is worth your investigation.”