Suits, masks and boots donned, we board the tractor’s trailer and begin a jaunty journey to the coast which, though visible from almost every point of the island, is blockaded from easy access by the pens of dairy farms. The trailer jolts us back and forth over muddy fields and stony boundaries, seatbelts not included. We grapple with the diesel smoke from the tractor, clanging cylinders, muck (a polite word for wet puddles of cow paddies) coating us as it splashes up from the drenched field tracks. We all laugh, feeling incredibly grateful that we didn’t take the locals’ advice to get changed into our drysuits once on the coastline. Without those drysuits, we would have been utterly coated to the skin in… well, kuh paddy!

The mists begin to clear and the proprietor of the ‘big house’ is waiting for us on the shore, with windbreaker flapping and maritime map in hand. I don’t say anything, but it all feels like a big underwater film production, with the local expert coming to help out the book smart but slightly clueless specialists. It makes me smile, which to everybody else merely seems to suggest a very polite American who is friendly despite being covered in cow poop and having been lurched to the point of nearly seeing those gleaming eyed sprats again. No television crew here… Just a shore-based archaeologist, kitted out in case of an underwater emergency, my dive partner – years more experienced in diving than even my own 15 – and now, the man from the big house. The man greets us warmly after last night’s meal and frivolities. As the west coast breeze whips through, reminding us of the impending autumn, he begins pointing out appropriate places to enter, suggesting the various rock formations that jut from the surf where we would be best placed to search for the Esperance’s remains.

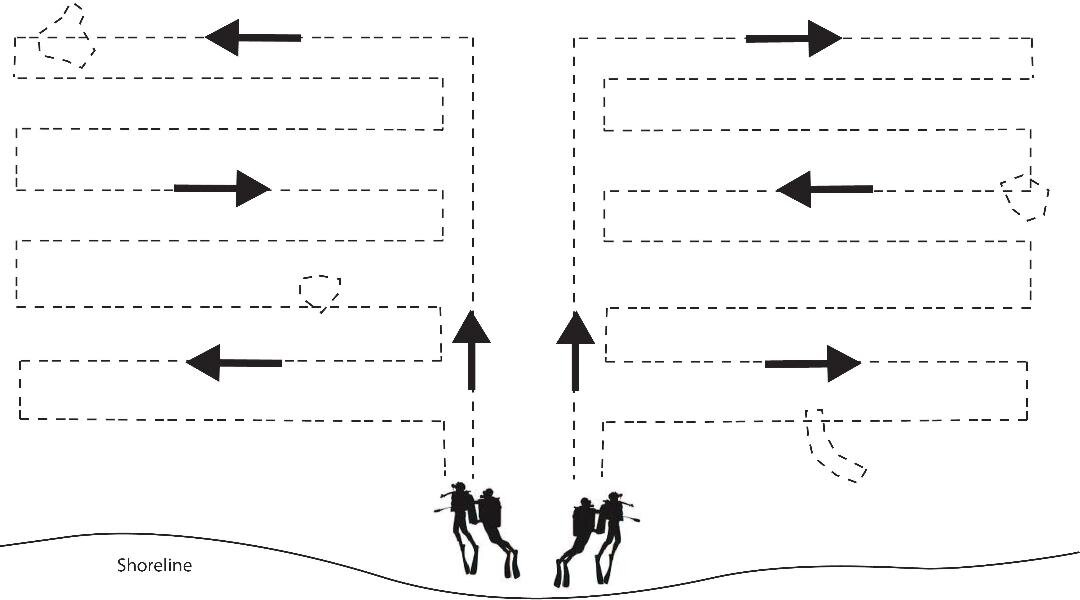

Likely locations for the Esperance had been suggested previously by professionals and amateurs throughout the century of its disappearance, but the actual whereabouts still remain a mystery. If we could find even a trace of it, we would be filling in a large piece of Gigha’s puzzling maritime past, and putting to rest (or to right?) stories about shipwrecked passengers who took refuge on the island. Our task is to make a series of coordinated passes across the kelp beds, out across a swathe of sand and finally to the Kartli (a known shipwreck). We bashfully try to rinse as much of the muck from ourselves as possible while he speaks to us; we want to seem neither concerned nor too comfortable covered in the island’s brown gold, nor do we want to wait until our actual dive to be free of the mess.

With approving final nods, a plan and safety checks, we begin our entry into the lapping waters of the Sound of Jura. We swim out on our backs to an agreed upon point, the sun now beaming across the water creating blinding reflections, and my dive buddy deploys a buoy to mark entry and exit points.

We had reached our dive site.

To be concluded…